There was a summer of discontent with publishers this year. Reopening old discourse is not a path to serenity, but there are things that have been left unsaid that can help us navigate both the current moment and prepare for what could happen in the future. Fortunately, a better understanding of the problem uses simple tools well within the grasp of any first year student currently finishing their Economics finals and can be demonstrated in Windows Paint.

The clearest statement of the problem would be that developers do not see publishing as being worth the terms publishers are asking for. This is a simple complaint to understand, since everyone wants to get value for money (or whatever else they’re giving up to get something). The solution is less simple. When the same complaint comes from consumers of games, developers feel (often justifiably) that the public only consider games sold at a loss to constitute fair value. Any analysis based on the two parties’ sense of fairness will not bring us any closer to a solution, but the problem of matching supply to demand is a well studied problem and games publishing is not a unique exception.

Most people are familiar with the concepts of supply and demand, even if they have never taken a Principles of Economics course. In fact, simply mentioning these comments probably brings to mind some image of a chart with two intersecting lines where a professor points to the intersection and argues that minimum wage or rent control is bad. It is a simple model of a market that is often misapplied, but its simplicity is a virtue, and the resulting insights often align with our intuitions and observations of the world.

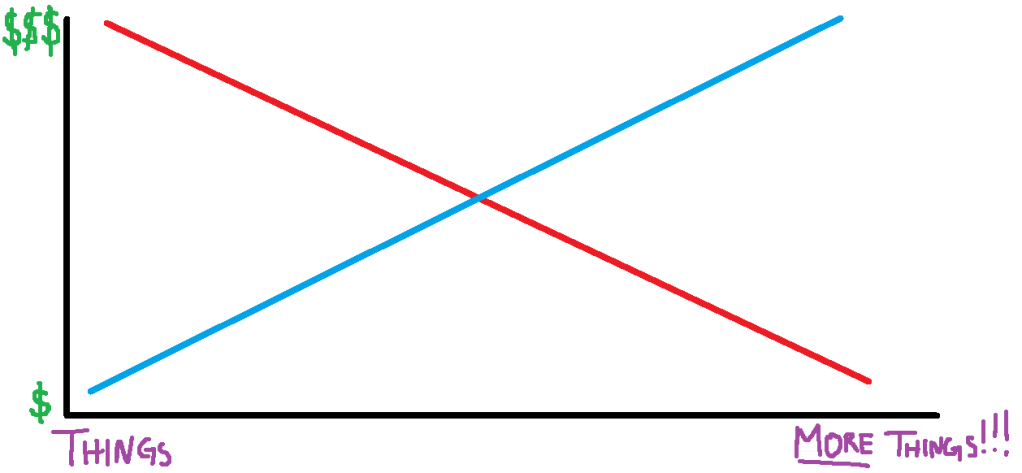

Each line on the chart describes a relationship between the price of a good or service and its quantity. One line describes the demand at a given price, while the other describes the supply. Considering our own experience as a shopper lets us guess which line is which.

We buy more (collectively and as individuals) when the price is low and less when the price is high. There is a price at which we won’t buy anything, represented somewhere in the upper left hand corner of the chart, and a point where we will load up on as much as we want, closer to the bottom right. From this it follows that the demand curve is the downward sloping (red in this case) line. Similarly, when we are offering a good or service, we offer more of it when we are paid more. When we are looking for work, there are some prices where we won’t accept the job, and others where we’ll work extra hours for the resulting overtime. Supply is the upward sloping (blue) line, since we wish to model the observation that we offer more of something when the price is higher.

The intersection of these two lines has a special status because it is the price where everyone who wants a good or service (at that price) is matched to someone offering it. A lower price has more demand than is satisfied, and a higher price results in more being offered than people want. The expectation is that the market will work towards this equilibrium as consumers bid up the price in order to obtain the scarce good or producers discount and stop producing the surplus.

Despite its special status, the equilibrium point doesn’t really tell us anything we didn’t already know. If we want to know the price of something we can go to the store and look at it or read a tweet complaining about it. The insights from the model come from our ability to play around and ask ‘what if’ questions when those two lines start shifting.

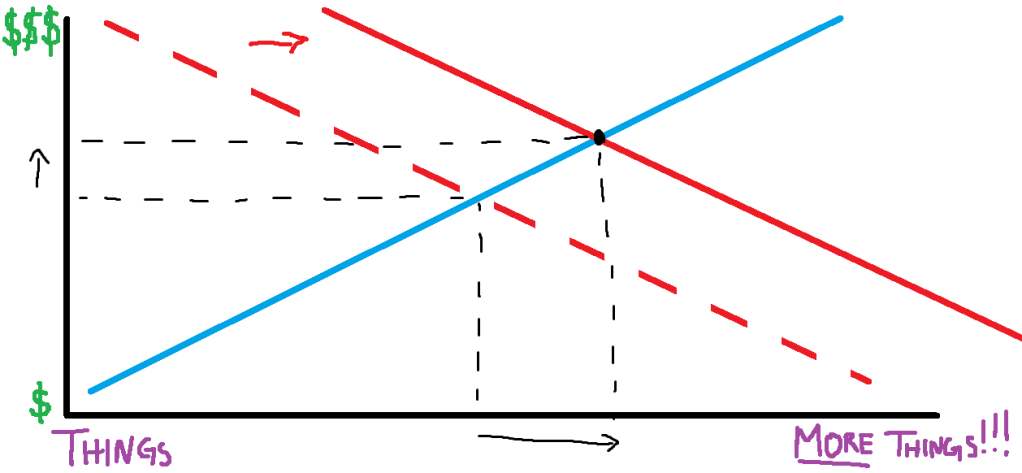

We have already observed that any point off the equilibrium represents a surplus or shortfall and that the expectation would be that we would move along the line to the equilibrium point. In contrast, a shift in one of these lines represents a change where the supply or demand for a good or service has changed at every price. If a popular article states that museum attendees are the best romantic partners, we might expect to see the demand for museums shift to the right as people buy tickets and existing members start finally showing up. Nothing has changed about the supply — the museums are still there and have the same capacity — but we should expect to see the price rise as the market gets back to the equilibrium point. (For those who are squeamish about what might be perceived as price gouging, consider that extra staff will be required to handle the surge in demand and need to be paid. Mercenary attitudes needn’t be embedded into the model, even if they happen to explain the behaviour of developers better than most alternatives).

Suppose instead that it becomes a lot easier to maintain a museum. This could be a better admission system, a drop in minimum wage, or maybe just a stronger social contract where we collectively agree not to molest the exhibits. This would produce a shift in the supply curve, effectively giving us more museum at any given price (or, equivalently, the ability to produce the same museum visits at a lower cost). We should expect a fall in price (and a consequent increase in attendance) as we move along the line to the new equilibrium. This outcome is the intuition behind the notorious supply side economics.

What if both things happen? What if the automated admission system coincides with a widespread museum mania? If the shift in demand dominates, then the price would go up, while a more dominant shift in supply would cause prices to go down. We cannot determine the direction of a price shift without additional assumptions, although we can say that museum attendance will increase since both shifts move in the same direction.

As fun as it is to push lines on a graph, we haven’t said much about publishing yet. It turns out we don’t require anything more than a slightly unorthodox way of thinking about the market for publishing to apply the exact same model.

We originally motivated this model by observing that the complaint about publishers is essentially a garden variety complaint about price. Developers may not go to the publishing store and ring up a publishing contract at the register, but the contracts do involve an exchange of things that have a monetary value (the distribution rights for an entertainment product, marketing support, even money itself). There is considerable variation among individual publishing contracts, but the same could be said for most of the goods and services that this model is successfully applied to. We are dealing with a general dissatisfaction with publishing terms, not just isolated complaints about specific contracts, and so apply a tool that looks at the market as a whole.

At some point in the past we had an equilibrium where developers who were demanding publishing services were matched to producers (publishers) who were willing to offer them at the prevailing price. Here the price should be thought of as encapsulating all the elements that go into a publishing contact, with terms that favour a publisher being a higher price and terms that favour the developer being a lower price. Assuming that today’s complaints reflect a genuine change in the market for publishing services, how might this have happened? The model does not allow for publishers to arbitrarily raise prices. Individual publishers that do so have competitors who will rush in to fill the gap and collusion between publishers would be an antitrust matter. Instead we are looking for shifts in the market that brought about the change.

On the publisher’s side, a lot has changed. A long period of inexpensive financing is long gone, the expectation of a permanent increase in the demand for games after COVID-19 didn’t materialize and has been replaced with an expectation of slowing if not declining spending on games. Publishers rely on a portfolio of games to offset the risks of a single title and usually convert a stream of income over time (the game’s lifetime revenue) into a lump sum payment to a developer to make a project. This means that publishers are particularly sensitive to the macroeconomic environment, every development of which has been negative. This is most appropriately modelled as a shift to the left in the supply curve, where developers are passing their increased costs to developers, cutting their appetite for risk, taking on fewer projects or, in some cases, exiting the market entirely.

In contrast, the demand for publishing services has only increased. Developers are realizing the importance of connecting with the audience for a game and realize the weakness of their exiting marketing efforts. Publishers are an attractive choice of specialist since they have a track record and can be a source of financing. “Get a publisher” is a newer, milder form of “get on Steam.” The number of developers has also continued to increase. Even as established studios conduct layoffs, first time and experienced developers are trying to put together projects and are seeking publishers to finance and distribute these games. Just like our example with museums, the demand curve has shifted to the right.

Either of these forces on their own would bring about an increase in the price for publishing services, and both in concert unambiguously raise the price. The deterioration in terms for developers is a simple product of too many people wanting an increasingly scarce thing. The only thing remarkable about the state of the market for publishing is how ordinary it is. “There are too many games” has been a common refrain for a while now, and it would seem that central banks agree. Unfortunately for some, they are now finding out that it was their games that were the unproductive ones that tighter monetary policy was intended to curtail.

Should we expect supply of publishing to increase at any time in the near future? Macroeconomic forecasting is difficult in the best of cases, but it would be better to see the past as anomalous, rather than some baseline we should expect to return to. What we imagine as the status quo is the product of unusually low interest rates, an expectation of a larger audience than exists, and the belief that adverse conditions would affect someone other than us. A transition from that past may be painful, but those past conditions are not something we should wish to return to. If there is going to be an increase in publishing services, it would be better to look for an overall expansion of the gaming space or an innovation in the publishing model itself, rather than a return to the old ways.

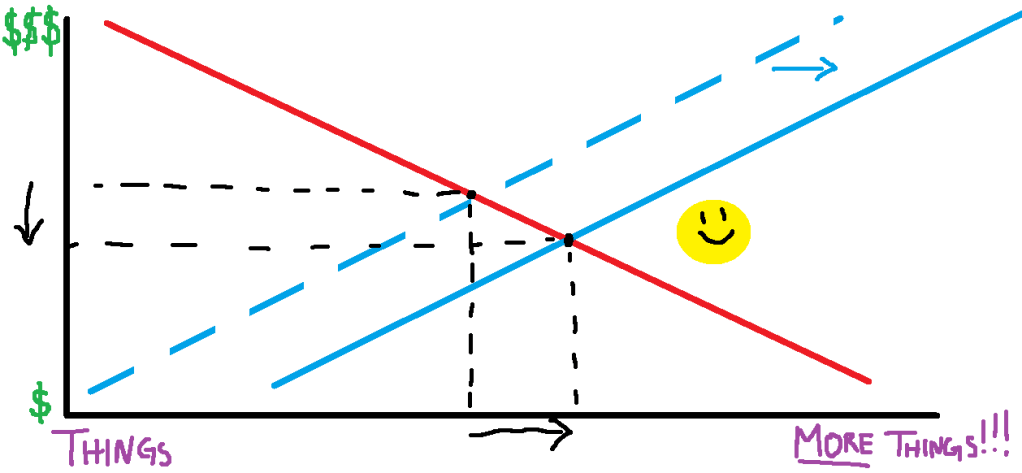

On the demand side, the only way to expect a decrease in the price of publishing is a decrease in the overall demand for publishing. There are plenty of developers who would accept this right up until it’s their turn to exit. In practice, the growth in the number of developers has proven resilient through a number of challenging times. However, it is worth keeping in mind that the number we should focus on is not total developers but rather the total number of developers looking for publishing services.

This is where we might find a path forward. Rather than hoping for the price of publishing to go back to what it was before, it may be better to ask if publishing is as essential as the complaints make it out to be. It does seem unusual to claim that publishing is somehow essential for independent games. If we accept the hypothesis, it might be worth asking how a developer might treat any other increase in costs. If a staff member asks for a raise, what usually follows is potentially uncomfortable set of conversations about what value they bring to the company, whether the firm can manage the increased cost, and how it might able to rearrange things in order to afford the increase or the departure of a key team member. What hopefully does not follow is a Twitter thread about greed. If publishers are so essential to the process, it might be better to ask whether the higher price is actually that unreasonable. If they’re not essential then they’ve priced themselves out of the market and developers should look elsewhere rather than wait for others to do so.

This is not to imply that a shift away from a reliance on publishers is easy. However “can we afford to do this?” is familiar territory for independent developers and is a more useful framing than seeing the current state of publishing as some kind of unprecedented catastrophe. From this angle, the complaint about publishers seems less about being able to make games at all and more about being able to make games developers had grown accustomed to. For better or worse, the shifting landscape has always been where both the risk and the potential for independent gaming lies.

The answers for navigating an uncertain environment aren’t particularly original. Other more experienced developers already advise that costs need to be kept under control, but it still needs to be said. The same goes for understanding a target market and how to reach them. If anything, the frustration with publishing terms provides developers a benchmark against which their own marketing efforts can be measured and make an informed decision about a publisher’s actual value. Ultimately, publishers are less willing to accept the level of risk they once did and are now returning it to developers. For the developers who are willing to use this as a catalyst to change their own development model, it also means that the publisher is returning the rewards of success.